Hiring Puzzle: Why Do Firms Decrease Hiring So Much in Recessions?

Key Takeaways

- Unemployment rate fluctuations observed in the data are much larger than what can be explained by traditional search models.

- Inspired by explanations that rationalize high volatility of the stock market through fluctuations in risk premia, we hypothesize that fluctuations in the unemployment rate might be driven by the same factor.

- While we find that fluctuations in risk premia indeed help, we also conclude that it cannot be the only driving force.

The unemployment rate fluctuates with the business cycle, rising and falling as economic activity changes: Businesses increase hiring during expansions (causing unemployment to decline), and they reduce their hiring efforts during recessions (leading to persistently high unemployment rates). Productivity shocks are the main driver of the business cycle, but are these productivity fluctuations also the sole driver of such employment cycles? In this article, I discuss my recent work showing that productivity fluctuations alone are insufficient to explain employment fluctuations.

Unemployment Volatility Puzzle

From a macroeconomic perspective, economists seek to understand business cycle fluctuations in unemployment rates for several compelling reasons. A primary concern is that cyclical unemployment represents wasted productive capacity. Unemployed workers tend to lose their human capital over time, diminishing the economy's future productive potential. Understanding these fluctuations is therefore crucial for designing policies that minimize such inefficiencies.

The primary framework for analyzing unemployment dynamics is the search model developed by Peter Diamond, Dale Mortensen and Christopher Pissarides.1 This model envisions an economy populated by workers and firms, where firms employ workers to produce output and pay wages. To hire new workers, firms must post vacancies. Workers exist in one of two states — employed or unemployed — with unemployed workers searching for jobs by pursuing posted vacancies. Their job search efforts may or may not result in employment.

The business cycle in the model is generated through productivity shocks, as is usual in the business cycle literature. The model's key insight is that an unemployed worker's probability of finding employment depends on the vacancy-unemployment ratio, known as the labor market tightness. Job-finding probabilities are high during expansions, when vacancies are plentiful and unemployment is low. Conversely, during recessions, fewer vacancies and higher unemployment lead to lower job-finding probabilities.

While this model successfully captures the directional relationship between economic conditions and unemployment — low unemployment during expansions and high unemployment during recessions — it falls short in explaining the magnitude of unemployment fluctuations. The model predicts much smaller variation in unemployment rates than what's observed in empirical data. This discrepancy between the model's predictions and real-world observations has become known as "the unemployment volatility puzzle." This is also referred to as the Shimer puzzle, after Robert Shimer's influential 2005 paper "The Cyclical Behavior of Equilibrium Unemployment and Vacancies," which first highlighted this limitation.

Solutions to the Unemployment Volatility Puzzle

A critical limitation of the standard model is its prediction that wages absorb most productivity shocks. During recessions, firms' initial inclination to reduce hiring when productivity falls is largely offset by rapid wage adjustments. This wage flexibility dampens the decline in hiring incentives, resulting in only modest reductions in job postings and, consequently, small fluctuations in unemployment rates.

This disconnect between theoretical predictions and empirical evidence has spurred extensive research in labor economics. Scholars have proposed various solutions, including alternative wage-setting mechanisms and model recalibrations. While some of these modifications successfully generate the observed unemployment volatility, they introduce a new problem: They predict implausibly large fluctuations in expected profits from hiring an additional worker.

The Business Cycle Link to the Stock Market

In the financial literature, economists have documented that stock market valuation also exhibits high volatility over the business cycle.2 This volatility and its underlying causes have been extensively studied.

By definition, a stock's value equals the present discounted value of its future dividend stream. Research has shown that dividends themselves remain relatively stable over business cycles. This contrast between highly volatile stock prices and stable dividends has become known as the excess volatility puzzle.3 Consequently, economists have concluded that valuation volatility must stem from changes in how investors value future dividends, a phenomenon captured by fluctuations in discount rates.

Two Puzzles, One Explanation?

Could changes in how firms value future payments explain the unemployment volatility puzzle? A firm's hiring decisions depend on how it values potential workers — specifically, the present discounted value of a worker's future contributions to the firm profits. If this valuation fluctuates significantly, firms might dramatically reduce job postings during recessions as the perceived value of new hires declines.

The financial literature has demonstrated that variation in discount rates successfully explains stock market fluctuations.4 This raises an intriguing possibility: Could the same valuation mechanism provide a unified explanation for both stock market volatility and the unemployment volatility puzzle? That is the question Jaroslav Borovička and I ask in our 2025 working paper "Risk Premia and Unemployment Fluctuations (PDF)."

Our Approach

Our analysis builds on extensive finance literature that guides the construction and estimation of a model for discount rates disciplined by financial data. Using this model, we investigate the required properties of firms' profits from new hires that would enable the search model to generate unemployment rate fluctuations matching empirical observations.

This novel approach (rather than directly modeling the firm's profit stream) offers two key advantages. First, it characterizes properties that any labor search model must satisfy to resolve the unemployment volatility puzzle successfully. Second, it serves as a diagnostic tool for evaluating existing models, illuminating the sources of their successes and failures.

New Channel

Analysis of the labor market search model enriched with fluctuations in discount rates reveals two potential resolutions to the unemployment volatility puzzle, each operating through distinct properties of the profit flow:

- High variance of expected profits

- High mean of the conditional variance of profits

The first property — high volatility of expected profit flow — implies that a worker's contribution to firm profits varies substantially over the business cycle: This profit is high during expansions but drops significantly during recessions. This represents the traditional channel that models without time-varying discount rates must rely on to explain the unemployment volatility puzzle.

The second property — high expected conditional volatility of profit flow — focuses on a mechanism that interacts with time-varying discount rates. Under this mechanism, workers generate stable profits during expansions. However, during recessions, the marginal profit becomes highly uncertain while potentially maintaining its average level. The profit could either exceed normal levels or fall far below them, but firms cannot predict which outcome will occur at the onset of the recession. This uncertainty leads risk-averse firms to significantly discount the value of new hires during recessions compared to expansions. In a model without time variation in discount rates, firms are not concerned about this uncertainty and hence it does not affect their hiring decisions.

The increased risk in profit flow during recessions may stem from several sources. First, sales may become highly unpredictable as customers abruptly reduce spending or postpone purchases, in contrast to the stable purchasing patterns seen during expansions. Second, firms' significant fixed costs (including facilities and core personnel) cannot be quickly reduced when revenue falls, forcing firms to absorb revenue volatility. Third, firms often resort to discounting their products during recessions to maintain sales volume, further destabilizing profit margins.

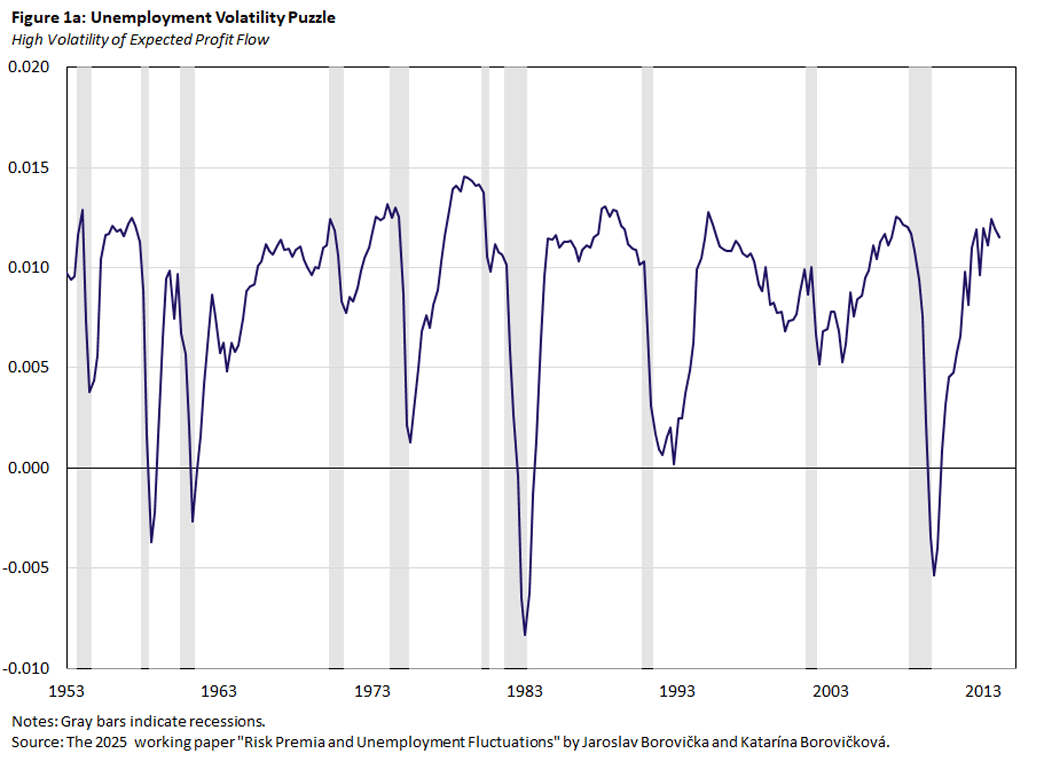

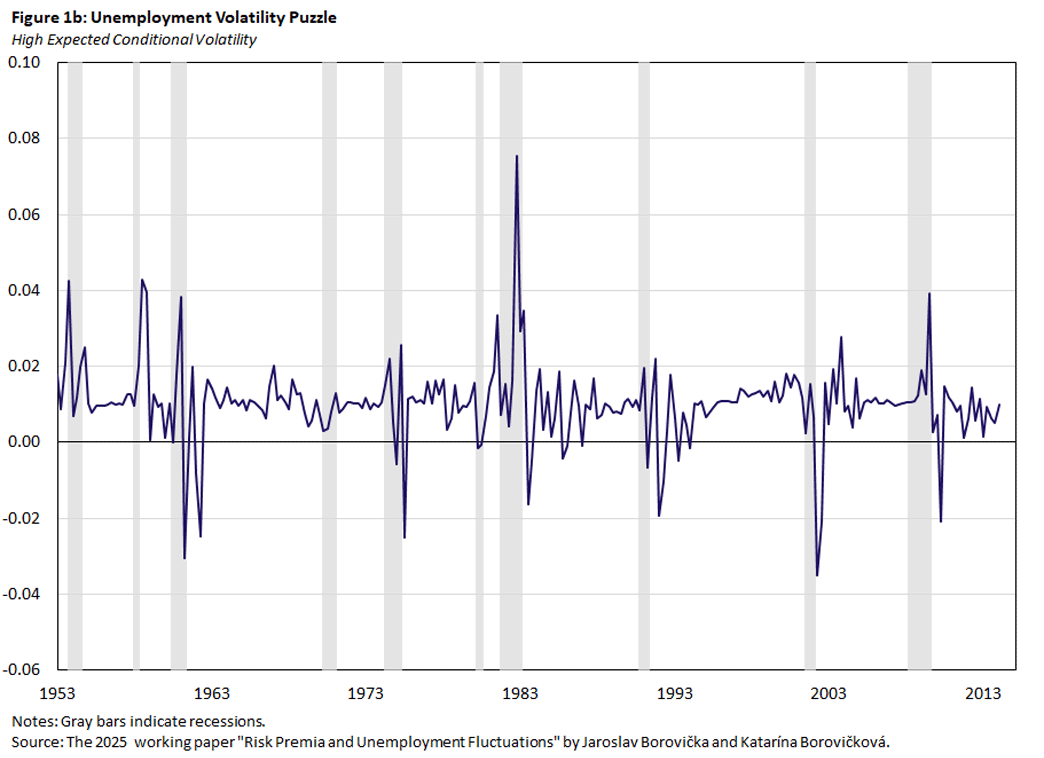

These mechanisms contribute to generating substantial profit volatility during recessions. Figure 1 illustrates these distinct forces through hypothetical profit patterns.

Figure 1a illustrates an example of profit flow driven primarily by the first channel: Profits remain consistently high during normal periods but systematically plummet during recessions (shown as the shaded areas). Figure 1b demonstrates the impact of the alternative channel: Profits maintain the same average level across both expansions and recessions, but their volatility increases dramatically during recessions, fluctuating between extreme highs and lows while remaining stable in normal times.

In a search model incorporating time variation in discount rates, either channel (or a combination of both) can resolve the unemployment volatility puzzle if sufficiently strong. Most existing explanations in the macroeconomics literature rely exclusively on the first channel, as these models typically feature only very weak concerns about risk on the firm side.

However, this approach requires implausibly high profit volatility — approximately 25 times the volatility of GDP — to rationalize the observed volatility of unemployment. The introduction of the second channel — which emerges only in models with an appropriately specified time variation in discount rates — reduces the burden imposed on the first channel. This raises a crucial question: How much can the second channel contribute to resolving the puzzle?

Our Findings

Our paper quantifies the trade-off between these two channels. Using an empirically plausible model of time variation in discount rates disciplined by financial data, we characterize a bound on all possible combinations of the two channels necessary for the model to generate observed fluctuation in firms' willingness to hire workers.

If we discipline mechanism 1 (volatility of expected profit flow) by the data, then mechanism 2 (high conditional volatility of profits) must also be present to generate unemployment fluctuations. The bound we derived tells us how strong mechanism 2 needs to be. Our main finding is that it must be stronger than what we can support in the data. In particular, the conditional volatility of firm profit would need to be 8.5 times higher than the riskiness of profits measured in the data.

This implies that mechanism 2 alone will not resolve the unemployment volatility puzzle. At the same time, this mechanism turns out to be important. If we discipline both mechanism 1 and mechanism 2 by the data, our model generates 50 percent of the unemployment fluctuations observed in the data, while it can generate only less than 5 percent if mechanism 2 is not present.

Measurement Challenge: Average Versus Marginal Profit

An important caveat to the calculations above deserves emphasis. When making hiring decisions, firms consider the so-called marginal profit, or the additional profit generated by a newly hired worker. This quantity cannot be directly measured in the data, as individual worker productivity and individual contributions to firm's total profits remain unobservable.

Instead, we measure the profit flow generated by the average worker, which can be calculated from observed data on firm profits and employment. While marginal profits likely exhibit greater volatility than average profits, the magnitude of volatility required by our analysis appears to be very high.

Conclusion

Returning to our central question: Can changes in the valuation of future cash flows explain both stock market volatility and unemployment fluctuations? Our analysis suggests a nuanced answer. While valuation fluctuations successfully explain stock market dynamics, they appear insufficient as the sole driver of variation in firms' hiring decisions.

Although this new mechanism contributes to resolving the unemployment volatility puzzle, a complete explanation likely requires additional factors. Based on our empirical analysis detailed in the paper, we suggest that combining this valuation channel with financial frictions may offer a promising direction for future research.

Katarína Borovičková is an economist in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

See, for example, Pissarides' 2011 paper "Equilibrium in the Labor Market With Search Frictions."

See, for example, the 1989 paper "Business Conditions and Expected Returns on Stocks and Bonds" by Eugene Fama and Kenneth French.

See the 1981 paper "Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to Be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends? (PDF)" by Robert Shiller.

See, for example, the 1988 paper "The Dividend-Price Ratio and Expectations of Future Dividends and Discount Factors" by John Campbell and Robert Shiller.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Borovičková, Katarína. (March 2025) "Hiring Puzzle: Why Do Firms Decrease Hiring So Much in Recessions?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-10.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the author, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.