Sentiment About Business Debt as a Leading Economic Indicator

Key Takeaways

- Changes in business-credit sentiment can have significant and long-lasting effects on the future path of U.S. macro variables, highlighting the importance of sentiment for the macro outlook.

- A positive credit sentiment shock can lower unemployment in the short run and boost GDP growth a few quarters after, generating higher inflation and federal funds rates.

Understanding the sources and transmission of financial distress in the economy is essential for macroeconomic stabilization policy. For example, policymakers and academics have both pointed to excesses in credit markets — including abnormally low risk premiums, misaligned incentives for risk taking, lax credit standards and excessive borrowing — as the main culprits behind the 2008-09 financial crisis.1 Since then, many questions have emerged regarding the role of credit factors in business-cycle fluctuations. Postwar data for multiple economies suggest that rapid growth in business or household credit and in asset prices are reliable predictors of a financial crisis within the next three years,2 and highlight the key role of corporate debt3 and household debt4 in explaining boom-bust cycles, financial crises and slow macroeconomic recoveries.

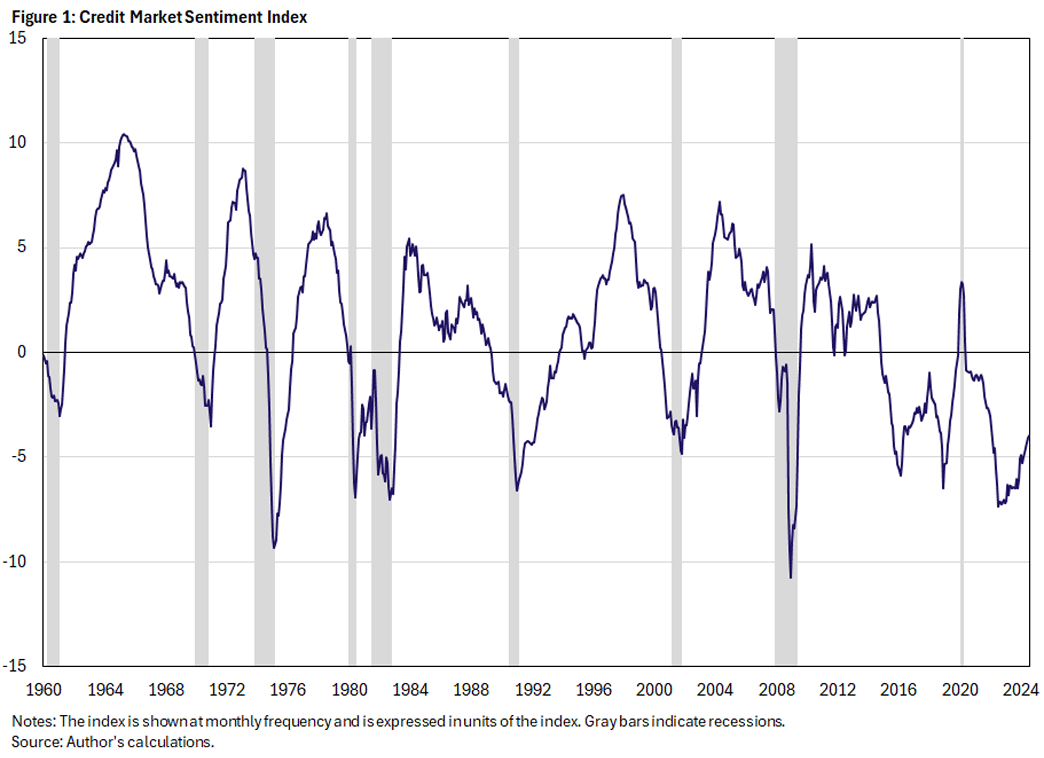

Using a new statistical model, the 2022 article "Introducing the Credit Market Sentiment Index" — co-authored by several writers of this article (Danilo, Gabriel, Horacio, Francisco and Egon) — estimated a factor summarizing conditions in U.S. credit markets and showed that it is strongly associated with business debt. We refer to this factor as the credit market sentiment index (CMSI).

In this article, we embed this index in a standard multivariate time series model to forecast the path of credit markets and key macroeconomic indicators. The results suggest that shocks to credit sentiment tied to business debt strongly forecast movements in real GDP growth, the effective federal funds rate and (to a lesser extent) price inflation.

Background on the CMSI

Credit market conditions are closely linked to real economic activity. The Great Recession highlighted the importance of household debt relative to business debt conditions. As outlined in the previous article, we develop a statistical framework that incorporates information from credit market indicators with strong links to business debt and real economic variables to isolate the conditions in the credit market that are independent of current economic conditions. This is the CMSI.

The construction of this index entails extracting information about credit market conditions from multiple credit market indicators that we expect to be strongly linked to business debt and that are both price-based and quantity-based. The model extracts three statistical factors that describe the state of the economy:

- The economic activity factor

- The CMSI

- The probability of an adverse economic state

In this article, we focus on the CMSI (shown in Figure 1), where a higher value reflects frothier sentiment. As depicted in the figure, the index identifies, for instance:

- The credit market froth before the Great Recession

- The sharp decline in credit sentiment as concerns about economic performance and financial risks surged in 2015

- The drop in the index among elevated uncertainty about the resiliency of the economy and the financial sector following the COVID pandemic

- The partial recovery of the indicator since 2022 as market participants' perceptions about severe downside risks in financial markets and the real economy gradually started to moderate

A Bayesian VAR to Study the Effects of Changes in Financial Sentiment

Next, we analyze how our measure of credit market conditions unrelated to current economic fundamentals may shape headline macroeconomic indicators. We use a rich time-series statistical model that incorporates the CMSI and five covariates:5

- Real GDP growth, represented by a synthesis of Stock & Watson monthly GDP series and the S&P monthly GDP series

- The unemployment rate

- Personal consumption expenditure price index (PCE)

- Personal consumption expenditure price index excluding energy and shelter (core PCE)

- The effective federal funds rate (FFR)

We specify a six-variable vector autoregression (VAR) and estimate it using Bayesian methods. As is standard in the literature, we assume a Minnesota prior that centers each variable's dynamics on its own lags.6 That is, the variables in our model are very persistent and largely independent of one another.7

We are interested in the effect of a shock that boosts credit sentiment on key macroeconomic variables and in forecasts for the paths of these macroeconomic indicators considering alternative future credit market tightness scenarios. We identify the shock by means of a recursive ordering of the variables. By ordering the credit factor first in the sequence of variables, we impose the assumption that the factor is independent contemporaneously from macroeconomic conditions. Our findings are robust to alternative orderings of the factor.

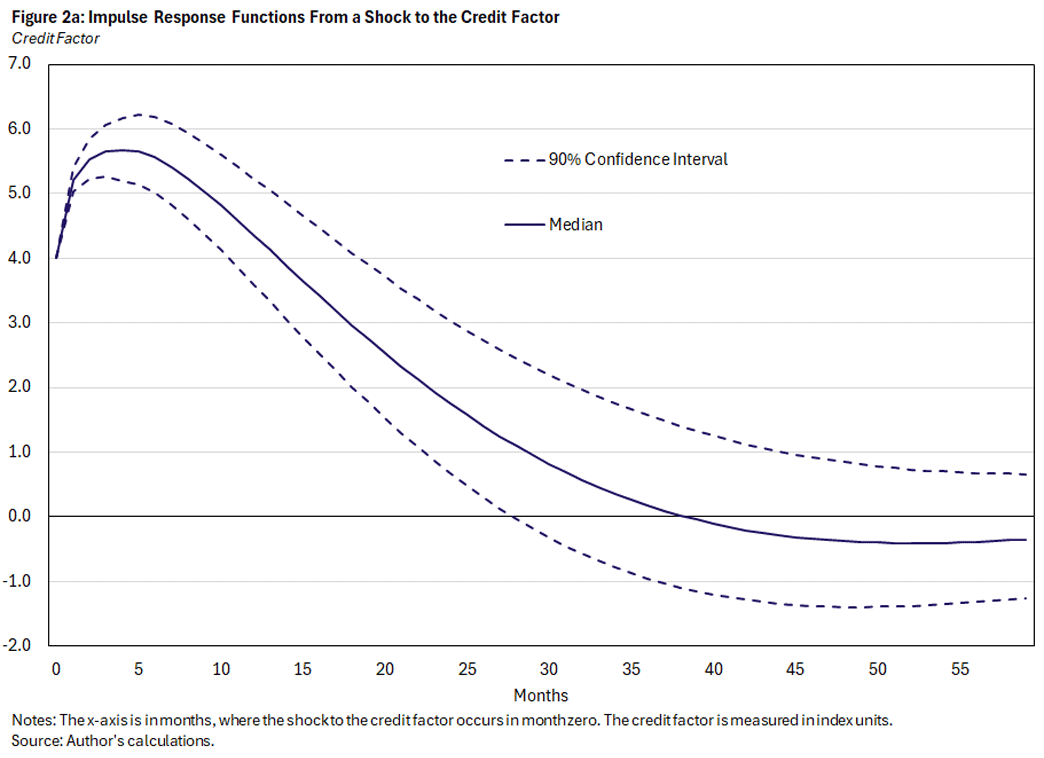

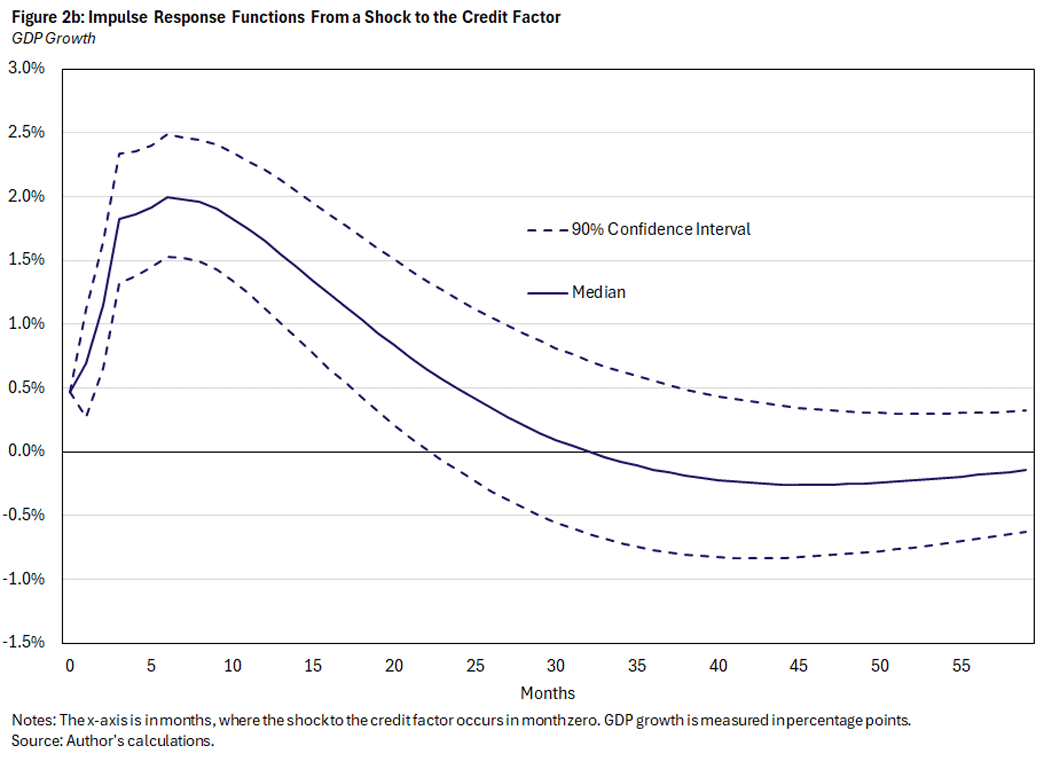

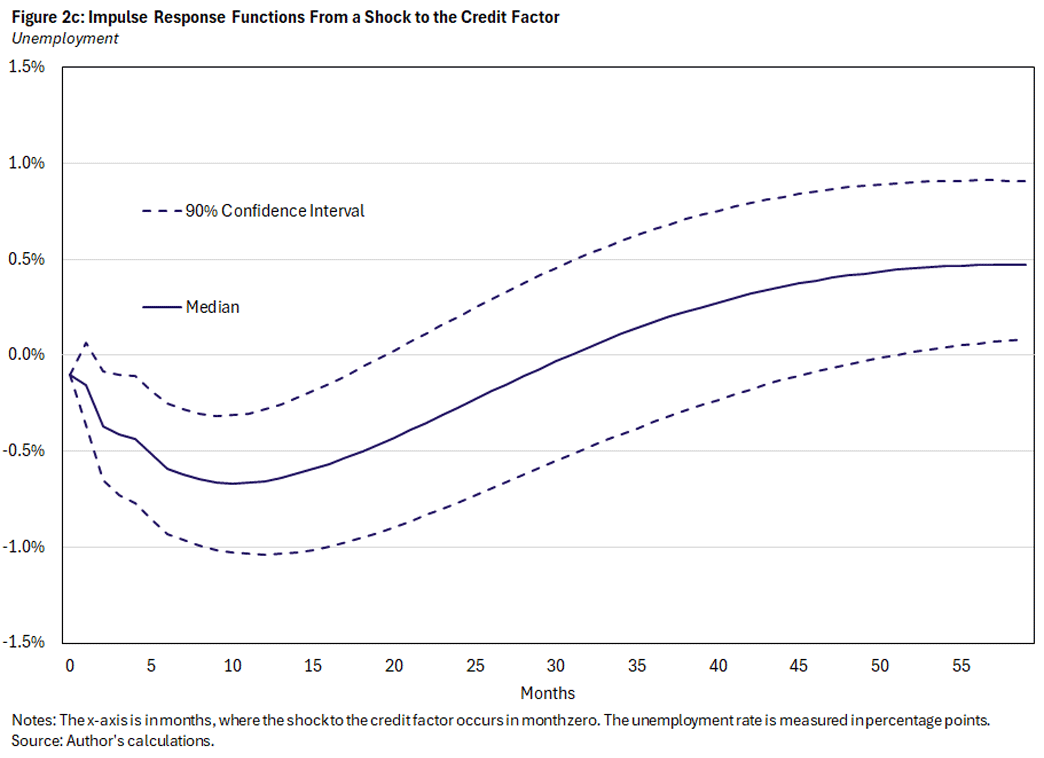

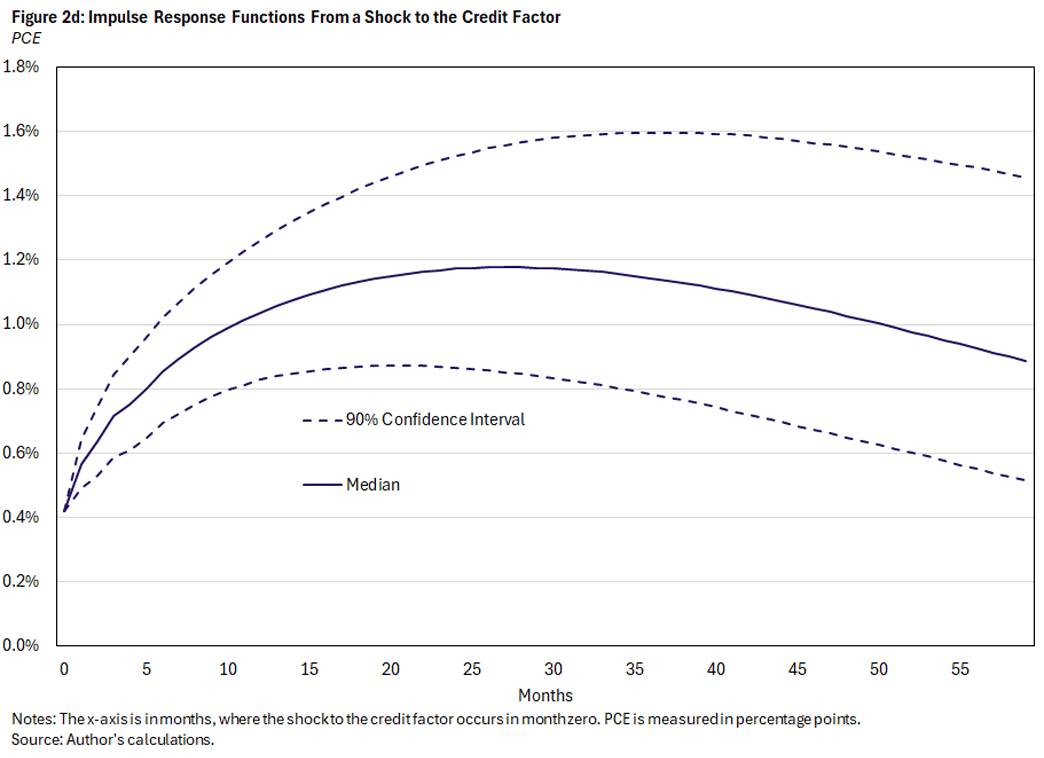

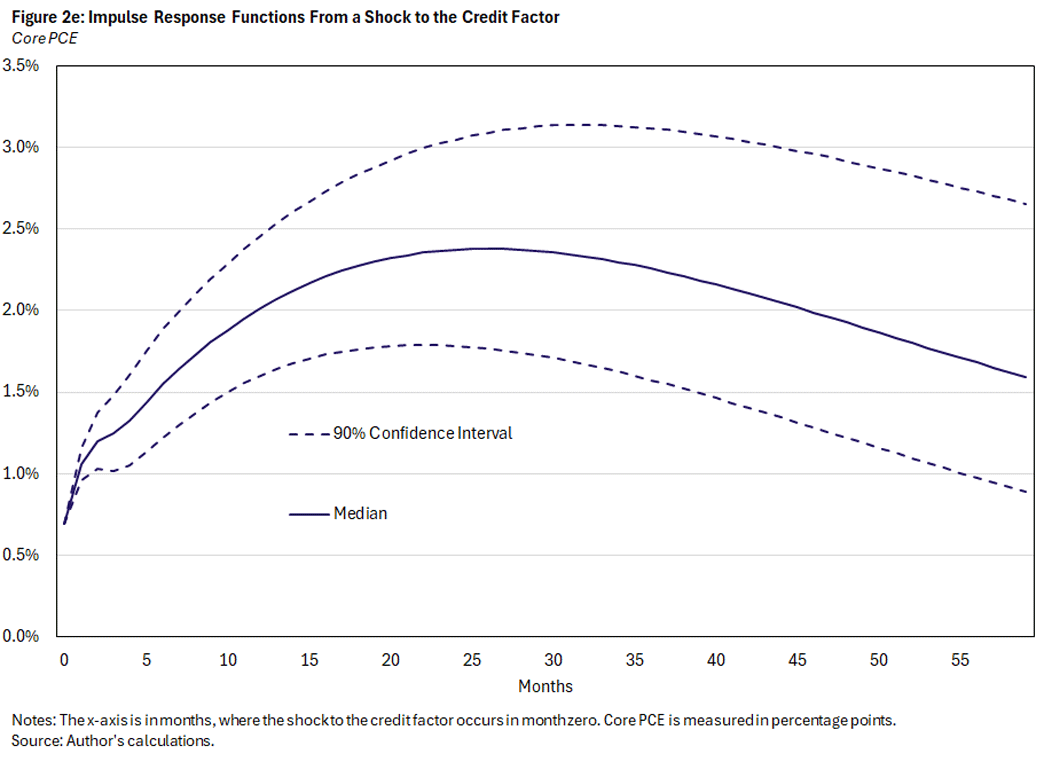

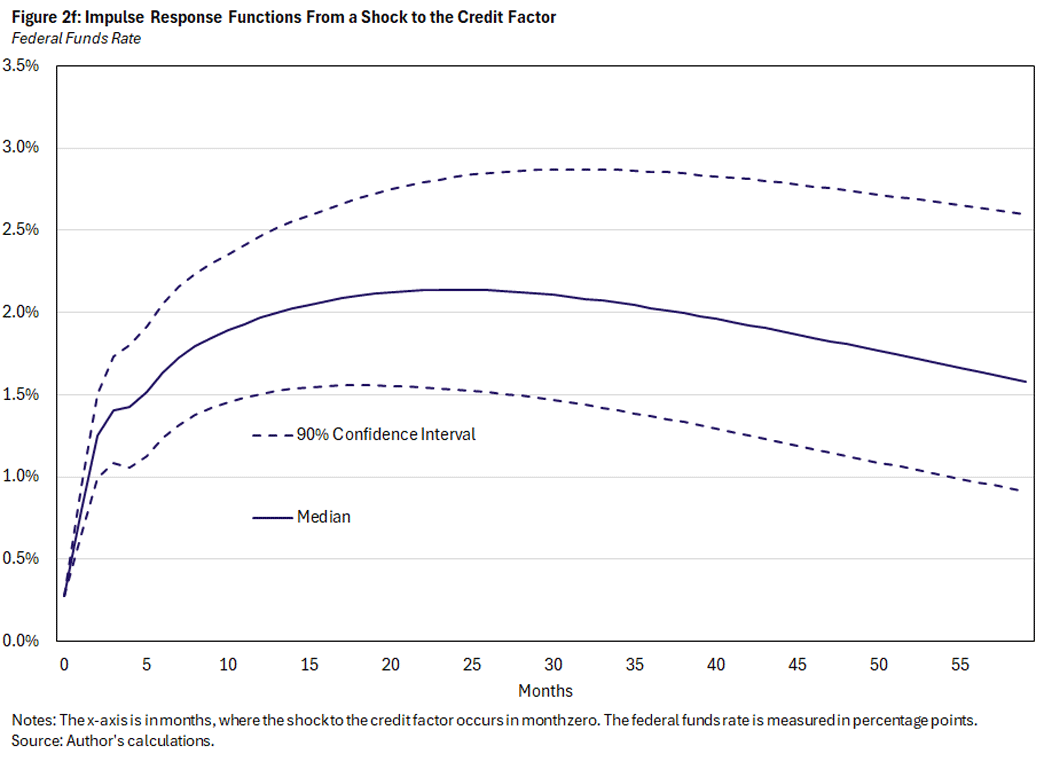

Each panel of the figure above illustrates how variables react to an increase of one standard deviation (four index units) in the CMSI. On impact — that is, in the period of the shock, which starts at month zero on the x-axis — the credit factor (Figure 2a) has a value of 4, and each of other variables immediately respond:

- GDP growth increases by nearly 0.5 percentage points.

- PCE and core PCE inflation increase by 0.4 and 0.7 percentage points, respectively.

- Unemployment and the federal funds rate have smaller responses on impact.

The CMSI peaks about four months after the shock and thereafter gradually declines, suggesting that credit market conditions remain frothier than prior to the initial shock even after two years. The dynamics of the CMSI are consistent with the idea that sentiment is a highly persistent object that can therefore have potentially long-lasting effects on the economy.

GDP growth responds positively to the easing of credit, peaking at six months with a cumulative increase of 2 percentage points. To account for higher GDP growth, the unemployment rate decreases by 0.6 percentage points six months after the shock, peaking at a 0.7-percentage-point decrease three months later.

However, the long-run effect on unemployment moves in the opposite direction: Five years after the sentiment shock, the unemployment rate response is a 0.5-percentage-point increase. The increase in output is accompanied by a delayed increase in inflation, with PCE increasing by 1.2 percentage points and core PCE by 2.4 percentage points two years after the credit factor shock. The model then predicts that the FFR will increase 1.4 percentage points within four months and over 2 percentage points within 18 months, as economic activity initially increases and then inflation increases.

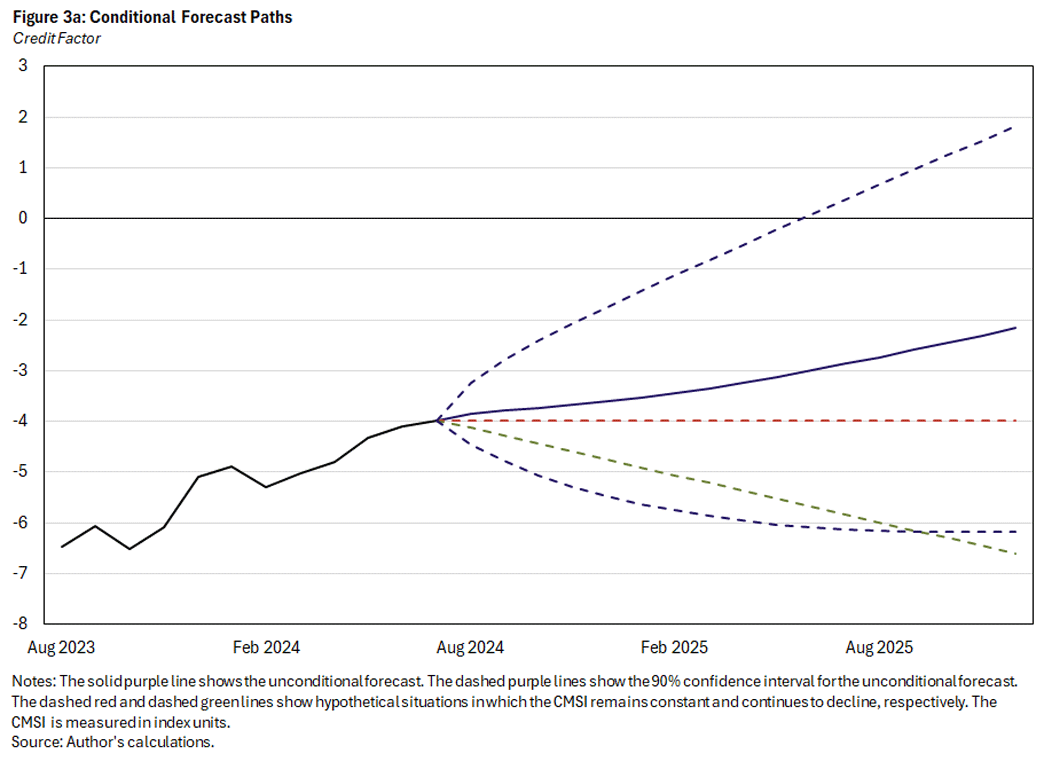

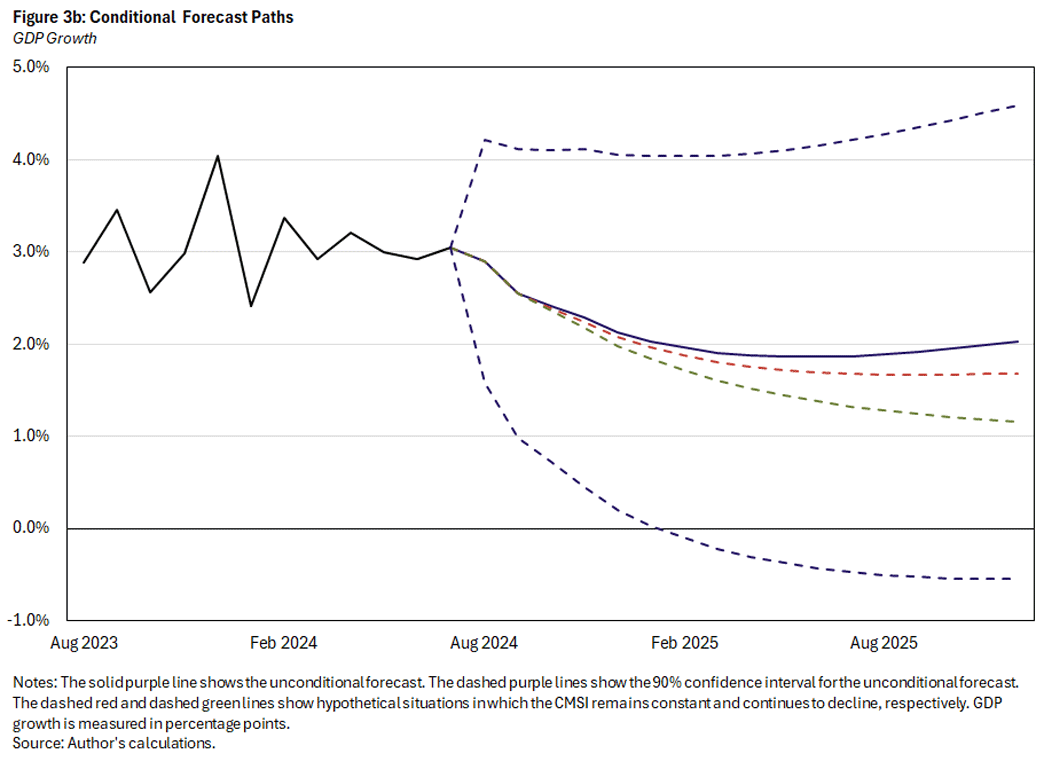

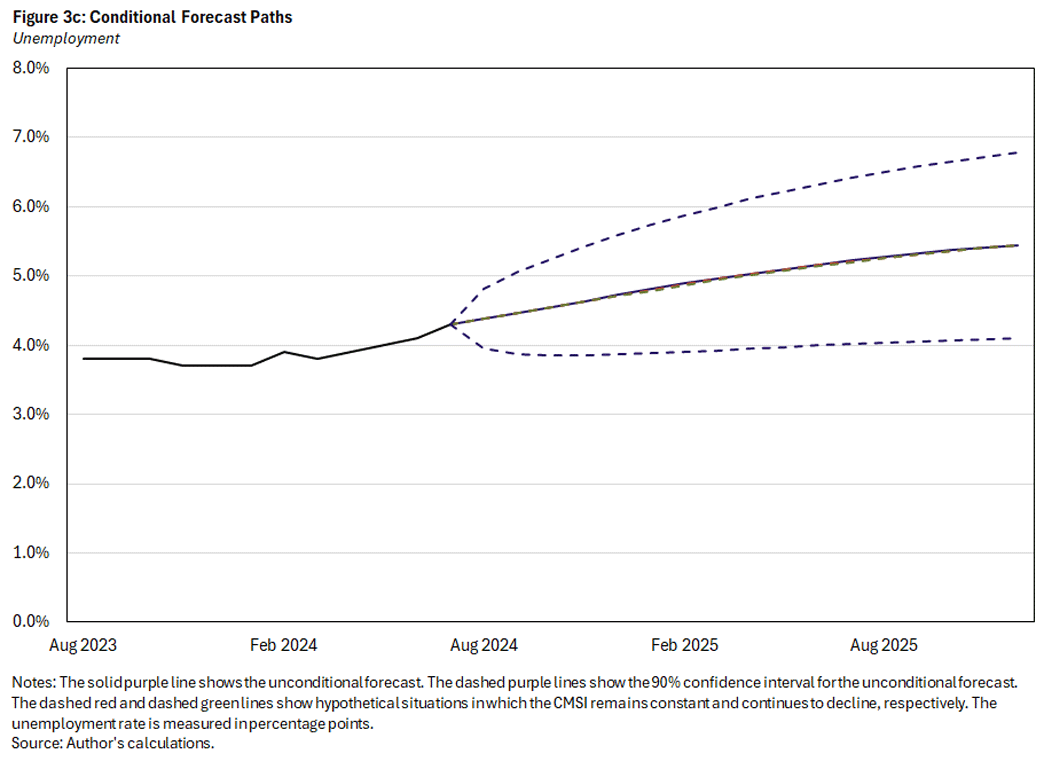

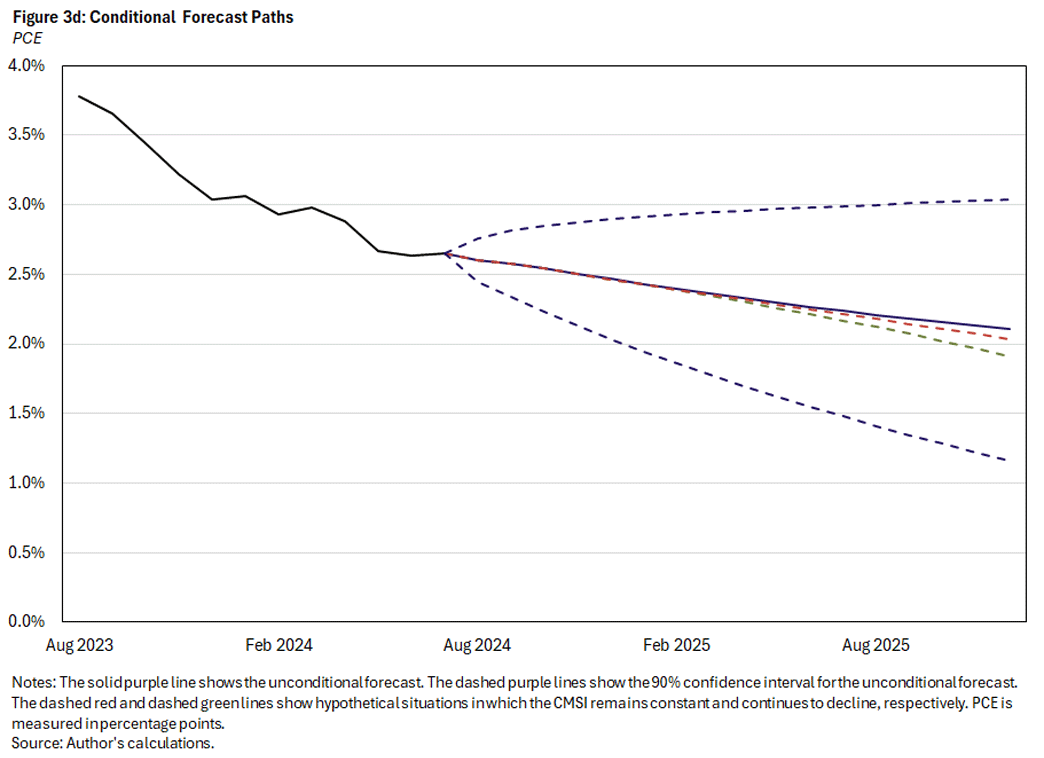

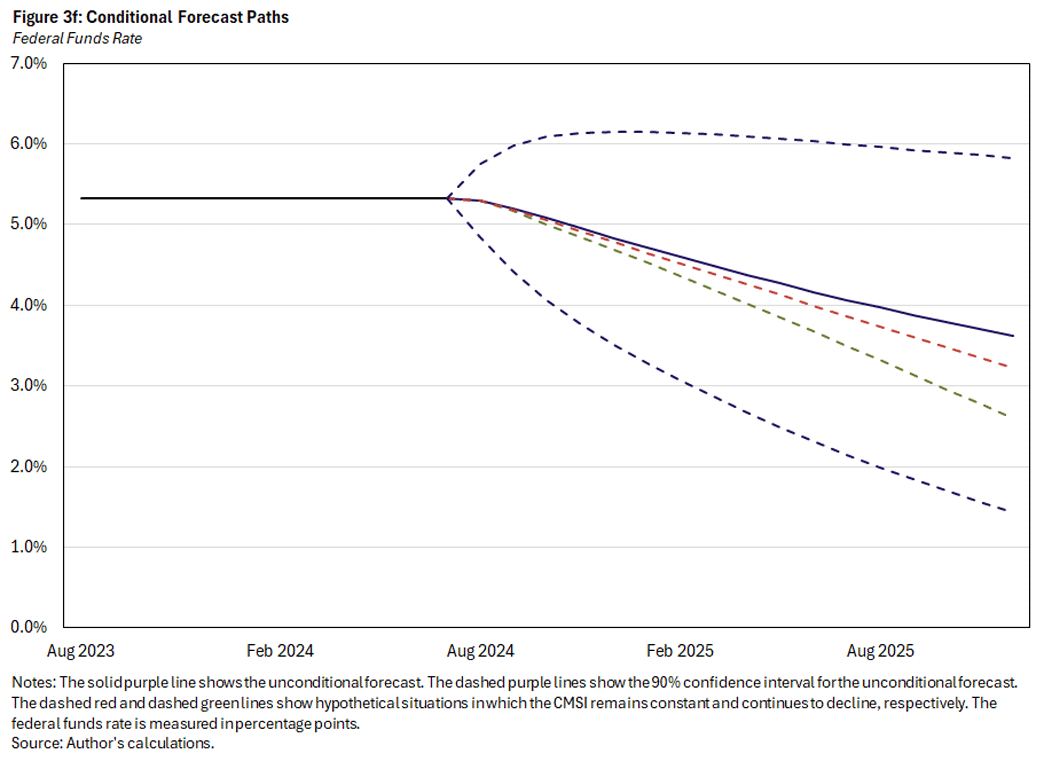

Another way to assess the role of credit market sentiment dynamics on the path of key macroeconomic variables is to examine the economic forecasts under different assumed paths of the CMSI. Each panel of Figure 3 above shows three forecasts. The first (solid purple line) is what the model predicts without restrictions, including a steady increase in the credit factor over the next two years. In the second scenario (dashed red line), we restrict the credit factor forecast to stay at its current level, and in the third scenario (dashed green line), we restrict the credit factor to decrease linearly.

In the median baseline forecast, GDP growth is expected to decrease initially then rebound to 2 percent by December 2025, PCE inflation is expected to decrease to just over 2 percent and be slightly below core PCE inflation, and the FFR is expected to fall by 1.75 percentage points.

In the second and third scenarios, the trajectories for PCE inflation, core PCE inflation and the unemployment rate remain mostly unchanged relative to the baseline. However, in the CMSI flat counterfactual, GDP growth is expected to stabilize around 1.7 percent, and the FFR is expected to decrease by nearly 2.5 percentage points. Furthermore, in the CMSI down scenario, GDP growth declines to 1 percent, and the FFR decreases by over 3 percentage points.

Conclusion

Using a Bayesian VAR, we show that changes in sentiment about credit conditions strongly tied to business debt can have significant and long-lasting effects on the future path of U.S. macro variables. A one-standard-deviation positive shock in credit sentiment can lower unemployment in the short run and boost GDP growth by up to 1.4 percentage points three quarters after, generating inflation and higher FFRs. Conversely, if credit sentiment were to worsen from its current state, we would expect output growth to cool, the unemployment rate to rise short term, and inflation and the FFR to fall.

These findings highlight the importance of considering the role of sentiment in credit conditions of businesses when assessing macroeconomic outlooks, as it can be a leading indicator of persistent changes in economic activity growth, inflation and changes in monetary policy.

Danilo Leiva-León is an economist and policy advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Thomas Lubik is a senior advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Gabriel Pérez-Quirós is the unit head of macroeconomic research in the Research Department at the Bank of Spain. Nathan Robino is a research associate in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Horacio Sapriza is a senior economist and policy advisor in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. Francisco Vazquez-Grande is a principal economist in the Macro Finance Analysis section of the Monetary Affairs Division at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Egon Zakrajšek is the director of research in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

See, for example, the 2018 paper "The Real Effects of the Financial Crisis" by Ben Bernanke.

See the 2022 paper "Predictable Financial Crises" by Robin Greenwood, Samuel Hanson, Andrei Shleifer and Jakob Ahm Sorensen.

See, for example, the 2024 working paper "Corporate Debt, Boom-Bust Cycles and Financial Crises" by Victoria Ivashina, Sebnem Kalemli-Ozcan, Luc Laeven and Karsten Muller.

See the 2017 paper "Household Debt and Business Cycles Worldwide" by Atif Mian, Amir Sufi and Emil Verner.

Real GDP, the unemployment rate, PCE and core PCE are seasonally adjusted. Real GDP, PCE and core PCE are month-over-month annualized rates. The unemployment rate is adjusted at a monthly frequency. The effective federal funds rate is calculated as a monthly average of the daily rate.

A Minnesota prior is a type of Bayesian prior distribution designed to shrink the estimated coefficients of model's lagged variables closer to zero, reducing the magnitude of the estimated relationships between variables. This helps to prevent overfitting, thus improving model stability and prediction accuracy.

We follow the method found in the 2009 working paper "Bayesian Multivariate Time Series Methods for Empirical Macroeconomics" by Gary Koop and Dimitris Korobilis. For the prior, we assume α has mean 0.9 (not quite a unit root), and the covariance matrix has hyper-parameters a1 = 0.5, a2 = 0.5, and a3 = 100.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Leiva-León, Danilo; Lubik, Thomas A.; Pérez-Quirós, Gabriel; Robino, Nathan; Sapriza, Horacio; Vazquez-Grande, Francisco; and Zakrajšek, Egon. (March 2025) "What Do Changes in Sentiment About Business Debt Say About the Economy?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-09.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.