How Do Banks Choose Where to Place Branches?

Key Takeaways

- We study the impact of geographic deregulation on where banks choose to locate.

- We find that the resulting patterns balance two forces for sorting in space: span-of-control sorting and mismatch sorting.

- Top banks fueled their growth by operating in the most profitable markets while maintaining a parallel presence in smaller markets to reduce reliance on expensive wholesale funding.

Prior to the 1980s, U.S. banks faced restrictions on where they could open branches, which essentially confined them to their home states. Subsequent deregulation over the next two decades eliminated these restrictions, drastically changing the landscape of the banking industry. Some banks grew rapidly, while many others exited the market due to either competitive forces or consolidation. The main effect of deregulation was to allow banks to open branches in new locations; as such, this episode provides a natural experiment to study the mechanisms behind the sorting patterns that emerge from spatial expansion. Said another way: How do banks choose where to locate?

My (Nicholas') recent working paper "Banks in Space" — co-authored with Ezra Oberfield, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg and Derek Wenning — proposes a spatial theory of bank organization that clarifies empirical trends from this deregulation period and spotlights the strategies underlying expansion.

Patterns Before Deregulation: Span-of-Control Sorting

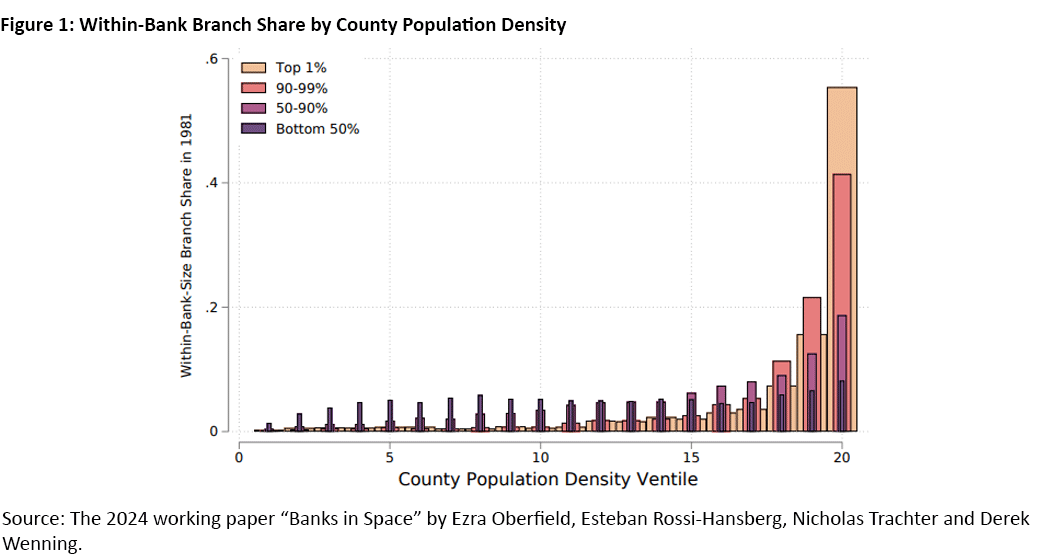

Let's examine the geographic distribution of banks in 1981, before the deregulation period. Figure 1 plots, for various sizes of banks as measured by the value of their total deposits, their share of branches over county population density. Each ventile represents 5 percent of all counties, in ascending order of population density. What we see is that the top 1 percent of banks are heavily concentrated in denser counties, with little presence in sparser counties. This pattern becomes less pronounced as bank size decreases: The bottom 50 percent of banks, for instance, have a relatively even presence across a range of population densities.

To grasp the intuition behind this pattern, we can think about the types of costs banks face when setting up new branches. First, they face fixed costs such as rent, which are inherent to location and don't vary from bank to bank. Then, there's a variable cost that is a function of a bank's size: The more branches, the more costly it is to manage this network of branches. Because large banks face higher managerial costs but the same fixed costs as smaller banks, they care relatively less about fixed costs. That is, fixed costs make up a smaller proportion of the overall cost of opening a branch for large banks.

The resulting sorting pattern is that larger banks — which are less sensitive to the higher fixed costs of locating in denser, more expensive and more profitable counties — have a larger presence in those places than smaller banks, as we saw in Figure 1. In the paper, this is termed "span-of-control sorting."

What Happened After Banking Deregulation?

How did this initial distribution change after deregulation? We measure the intensity of span-of-control sorting by how much the average local population density across a bank's branches increases with bank size. That is, span-of-control sorting sees large banks locating disproportionately in dense counties, and we observe the degree of this disproportionate concentration. Let's look at how this measure evolved over time.

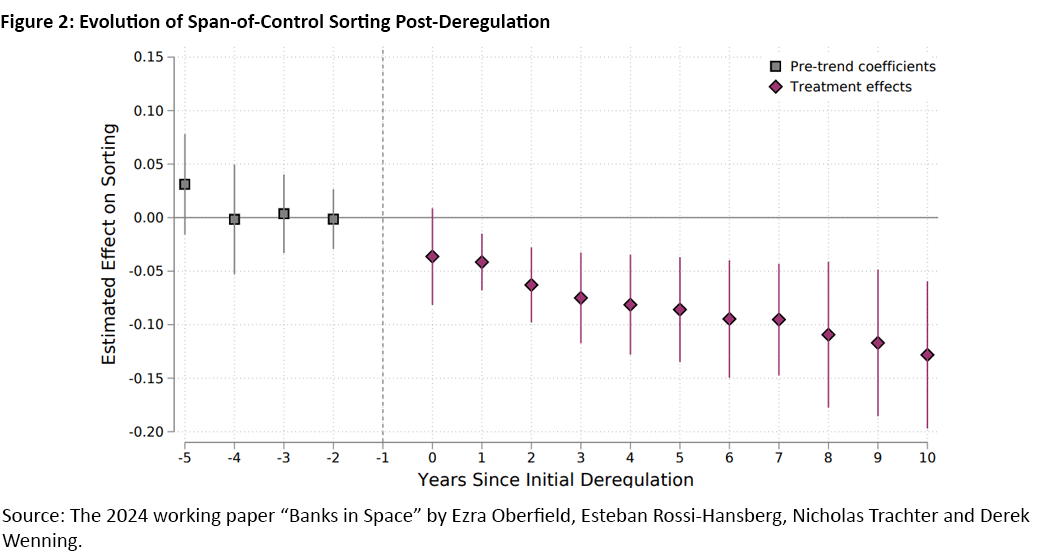

Figure 2 displays an event study, where the "event" is a state first opening its borders to out-of-state banks. Each plotted point represents how much the intensity of span-of-control sorting changed compared to the year before the event (indicated by the dashed line). The intensity of sorting in the five years before initial deregulation is relatively constant, but afterward, there's a marked and statistically significant decline that persists for at least 10 years.

In response to deregulation, span-of-control sorting weakened. Clearly, then, as banks expanded spatially in the 1980s and 1990s, they had multiple strategies in mind beyond simply continuing to sort into the largest markets in new states.

Modeling Bank Location Decisions

In exploring sorting strategies, the paper models where banks choose to locate. In the model, four forces characterize this choice:

- Banks prefer to place branches near their headquarters.

- Banks enter locations of varying density depending on the relative importance of different cost factors (leading to span-of-control sorting).

- Banks try to match the location demand for loans with their need for deposits.

- Banks that invest in their loan (deposit) appeal to consumers are incentivized to open branches in areas with high loan (deposit) demand.

Let's focus on the third force, which arises from features specific to the banking industry. The core business of a bank is to lend money and fund those loans through local deposits. However, the demand for loans and supply of deposits varies geographically: Urban centers and industrial hubs, for instance, tend to be loan-heavy due to high levels of business activity, real estate development, etc. If local retail deposits don't match loan demand, banks must look elsewhere for funding to close the gap. Sources for this wholesale funding include Federal Reserve funds, time deposits and brokered deposits, but these funds tend to command a higher interest rate than retail deposits.

Because of the extra expense, banks would like to minimize using wholesale funding by placing branches in locations where there's a good match between their funding needs and the local relative demand for deposits and loans. This force for sorting geographically — whereby banks reduce the mismatch between total deposits and loans — is labeled "mismatch sorting" in the paper.

A Mechanism of Dual Forces

Note that a tension emerges here: We established earlier that dense urban locations are highly profitable and attract the largest banks. But these same areas also tend to be loan-heavy, cutting into profits by forcing banks to use wholesale funding more intensively. This tension is exactly the driving factor behind the weakening sorting pattern seen in Figure 2.

Before deregulation, top banks — which disproportionately located in loan-heavy areas — were constrained in space and couldn't enter less-dense counties with more abundant deposits. They took advantage of the post-deregulation landscape to expand into these locations and gain access to cheap retail deposits, which they could then transfer to operations in more profitable lending markets. Since deposit-heavy locations are less dense, the result is a reduction in span-of-control sorting. Although span-of-control sorting was important both before and after deregulation, mismatch sorting significantly weakened its extent.

Using data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the paper tests for empirical evidence supporting this theory. Among other facts, the paper documents that:

- Low-density counties are indeed more deposit-heavy than high-density counties.

- Banks headquartered in loan-heavy locations do use more wholesale funding.

- These banks were indeed more likely to expand into deposit-heavy counties following deregulation.

- Expansion of top banks primarily occurred through covering more counties rather than adding more branches per county.

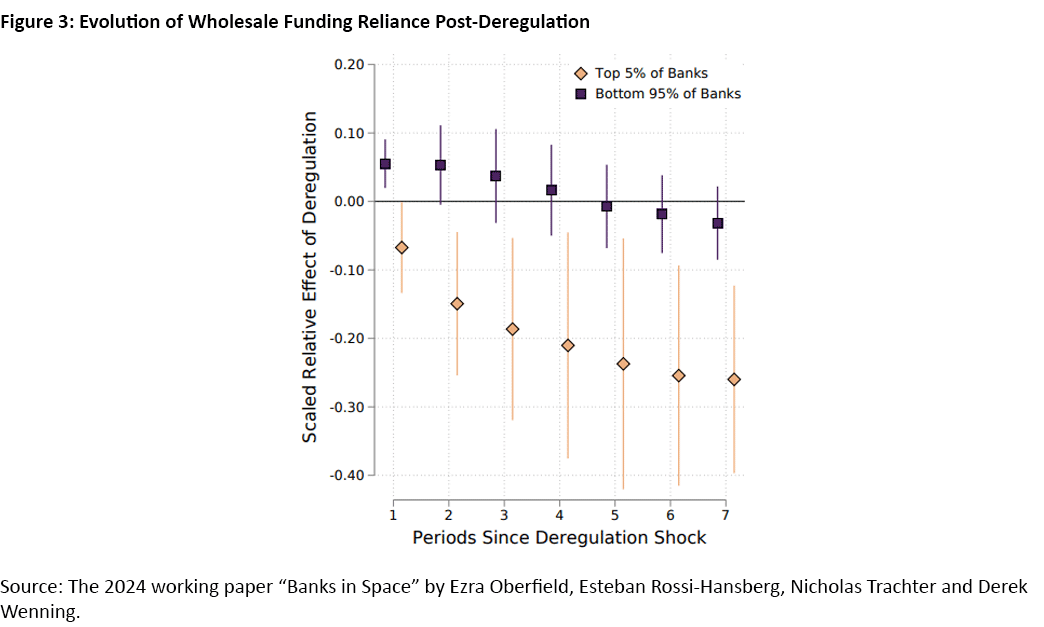

All the above aligns with the proposed mechanism. Moreover, Figure 3 plots the effect of the deregulation shock on wholesale funding reliance for two size classes. Each point represents the evolving difference in wholesale funding use between a bank with average pre-deregulation use and one with pre-deregulation use one standard deviation higher.

While the bottom 95 percent of banks see very little impact, large banks that use wholesale funding more intensively quickly and strongly decrease their use relative to the average large bank, an effect that's persistent for at least seven years. This lends support to the theory that deregulation relaxed liquidity constraints for banks, allowing them to raise deposits through branching and reduce their use of wholesale funding.

Conclusion

Geographic deregulation of the banking industry in the 1980s and 1990s unfolded in a way that highlights dual forces for the spatial sorting of banks: span-of-control sorting and mismatch sorting. The starting point was an industry in which top banks had headquarters in dense counties with an abundance of investment opportunities but relatively few deposits, making them reliant on expensive wholesale funding. Regulation had prevented these banks from optimally balancing their loan-to-deposit ratio, and upon being able to expand into new locations, they strategically positioned themselves to take advantage of profitable loan markets while minimizing the funding costs of doing so. This ability of top banks to operate in the most profitable markets with minimal reliance on wholesale funds because of their parallel presence in smaller deposit-heavy markets was the foundation of their success.

Lindsay Li is a research associate and Nicholas Trachter is a senior economist and research advisor, both in the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

To cite this Economic Brief, please use the following format: Li, Lindsay; and Trachter, Nicholas. (February 2025) "How Do Banks Choose Where to Place Branches?" Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Economic Brief, No. 25-06.

This article may be photocopied or reprinted in its entirety. Please credit the authors, source, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and include the italicized statement below.

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.

Receive a notification when Economic Brief is posted online.