Inflation Expectations: On The Move Again?

Typically, monetary policymakers don't need to react to all price shocks. Some price movements — such as those driven by extreme weather, oil price spikes or a one-time adjustment to tariffs — are expected to have temporary effects and are often prime candidates for policymakers to "look through" when deliberating on the stance of policy.

One exception is when inflation expectations (particularly those for longer-term inflation) begin to adjust in response to short-run price movements, raising the risk that temporary price increases lead to persistent effects on inflation. In this week's post, we examine some recent measures of inflation expectations to judge whether this risk might be taking shape in recent data.

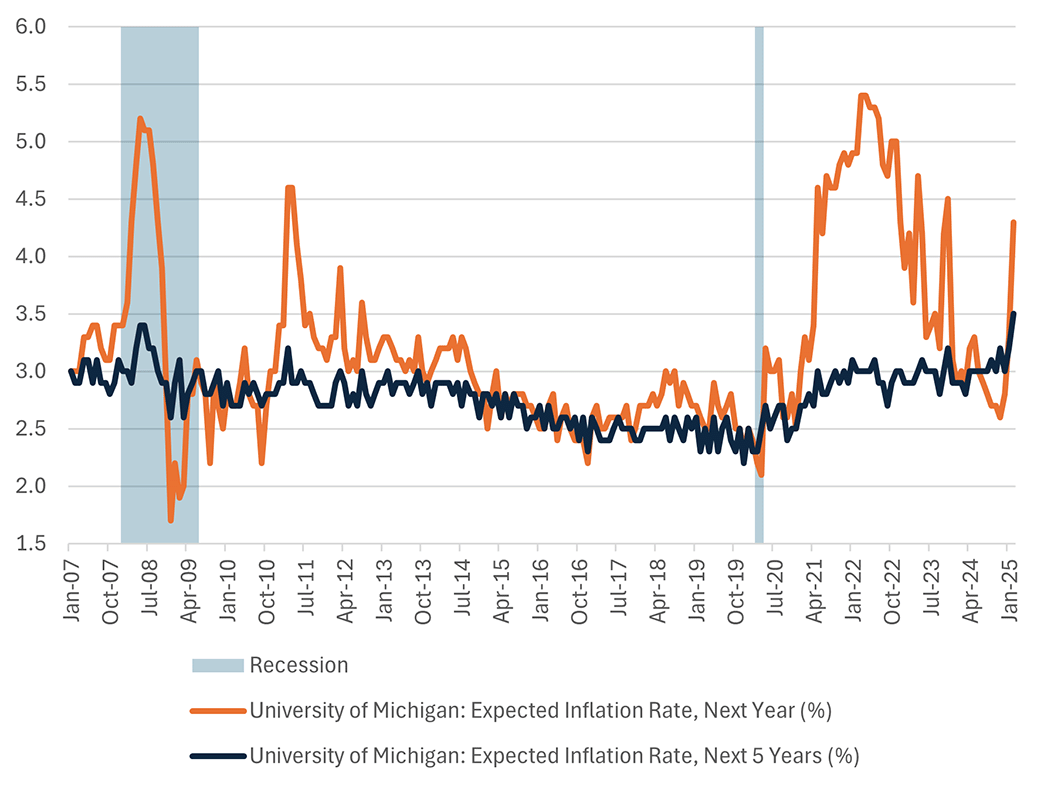

Figure 1 plots one-year-ahead and five-year-ahead inflation expectations from the University of Michigan's Surveys of Consumers. In February 2025, households' inflation expectations over the next 12 months rose for the third straight month. They now sit at 4.3 percent, which is the highest mark since November 2023. This increase may be partly attributable to tariff-related price increases, which survey director Joanne Hsu suggested also contributed to a decline in the survey's consumer sentiment index in February.

Worryingly, longer-run inflation expectations rose to 3.5 percent in February, the highest mark in nearly 30 years (April 1995). The survey question associated with this series is "By about what percent per year do you expect prices to go up or down, on the average, during the next 5 to 10 years?" While households may not be interpreting this question as asking for "forward inflation expectations" — that is, the average of inflation in years 6-10 over the next 10-year period — it's notable to see such a large increase in longer-term inflation expectations, given that tariffs would only be expected to have a temporary inflationary impact.

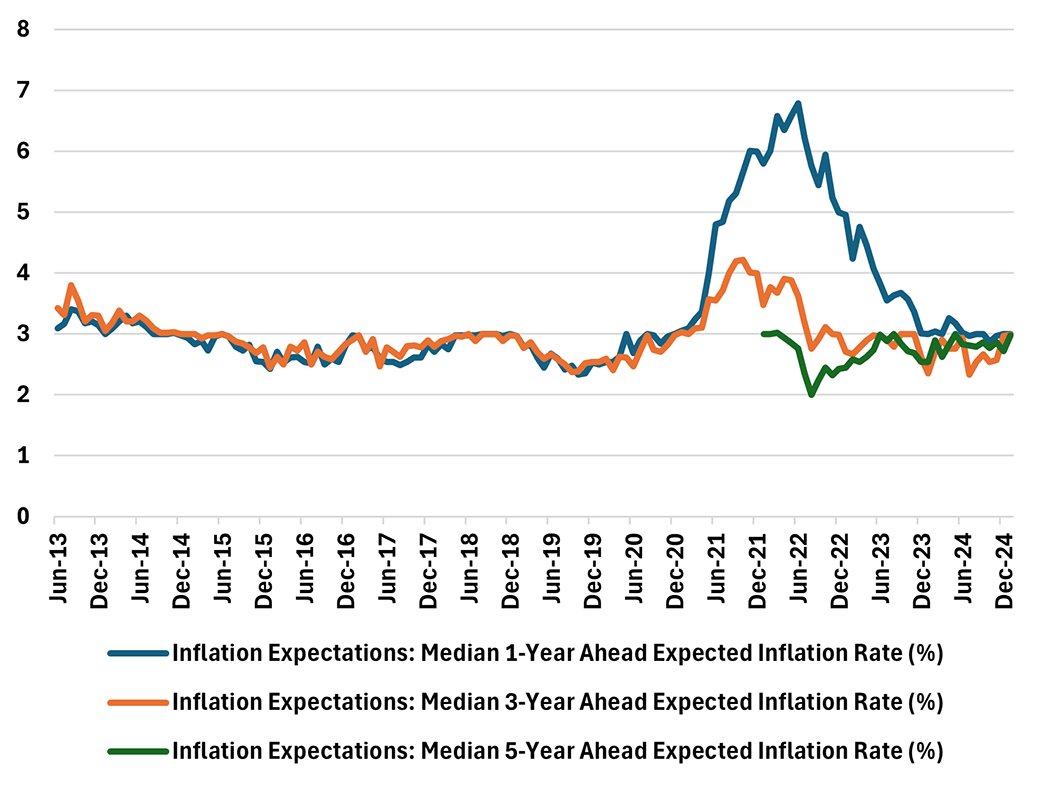

The latest monthly readings of the New York Fed's Survey of Consumer Expectations (SCE) — which includes another measure of households' inflation expectations — may also point to rising longer-term inflation expectations. According to this source, three-year inflation expectations jumped by more than 1 percentage point in December and remained at that elevated level in January, while five-year inflation expectations increased in January to their highest level in over six months. On the other hand, after zooming out from the most recent monthly movements in the survey, Figure 2 reveals that current levels of one-year and three-year inflation expectations appear similar to their prepandemic levels.

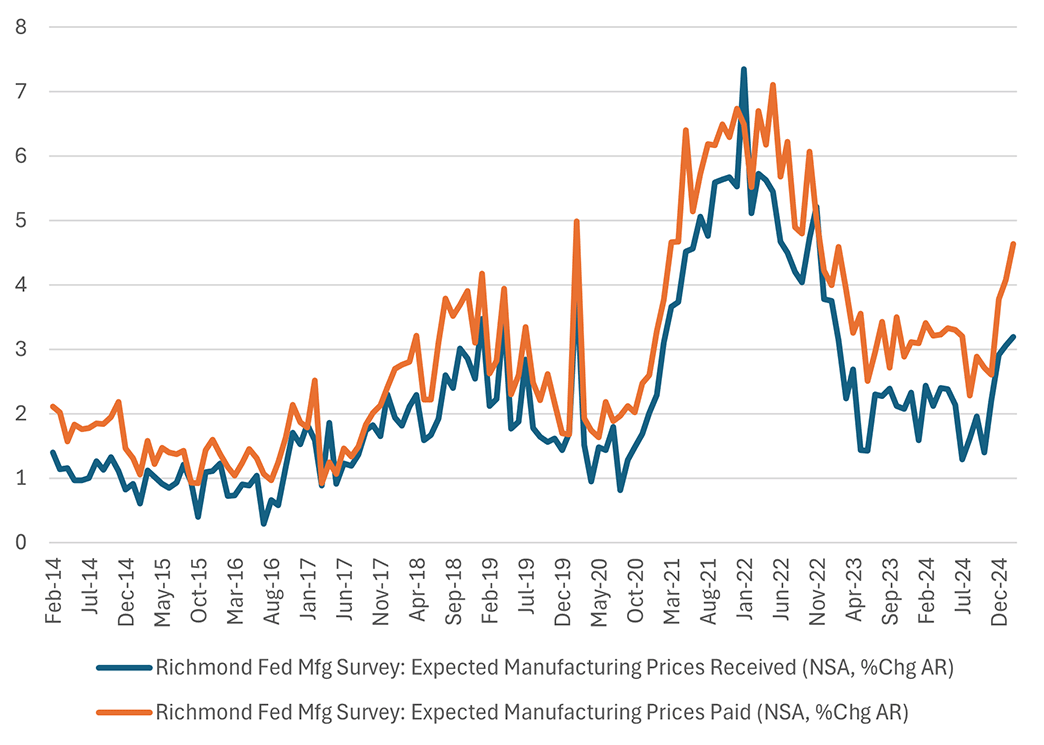

Businesses' inflation expectations are on the rise as well, at least in the short term. Figure 3 shows readings from the Richmond Fed's manufacturing survey through February. The survey shows that expectations for growth in prices received over the next 12 months rose for a fourth straight month, reaching 3.19 percent year over year, the highest level since January 2023. Expectations for growth in prices paid rose for the third straight month, reaching 4.64 percent year over year, the highest level since November 2022.

While Fifth District manufacturers expect growth in both input prices and prices charged, the Richmond Fed's services survey from February indicates that services businesses may not be as able to pass expected higher input costs through to their customers. Figure 4 shows that Fifth District services businesses expect input price growth over the next 12 months to grow by 5.09 percent, the fastest rate since April 2023. However, growth in prices received from customers is expected to rise by 3.62 percent, similar to the average response received over the preceding 18-month period (3.59 percent). The disparity between these responses illustrates that some businesses may be able to (and others may be forced to) adjust margins in response to rising input costs: Not all input cost increases will translate to higher prices to customers.

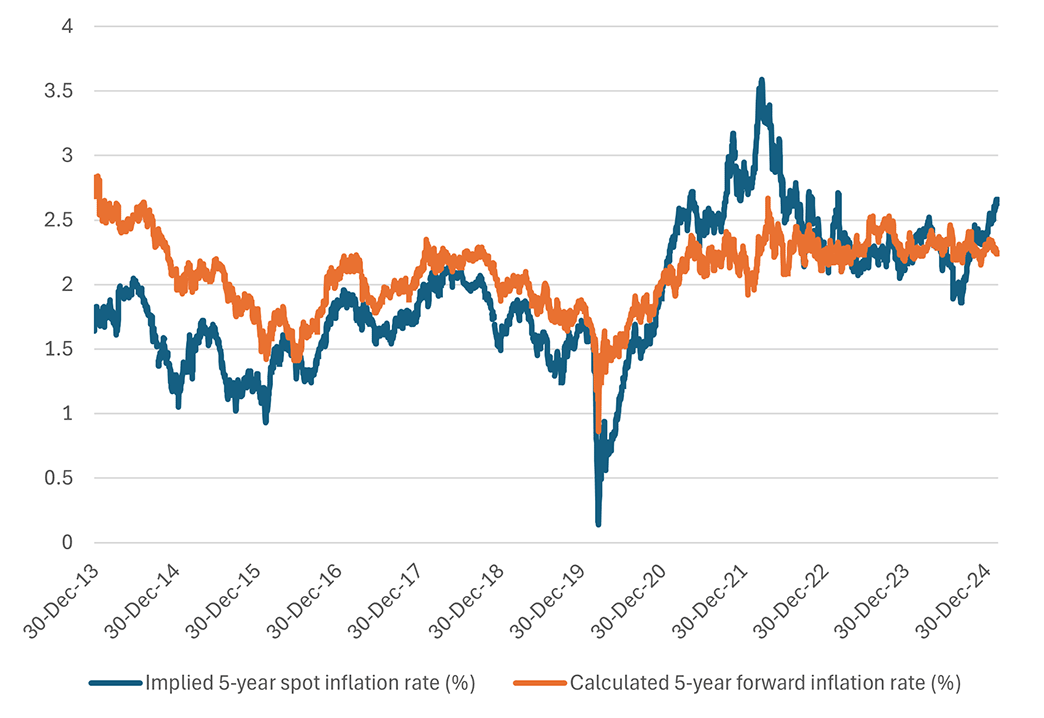

Finally, Figure 5 illustrates two measures of inflation expectations of financial market participants: five-year inflation compensation and five-year-forward inflation compensation. The latter captures five-year inflation expectations five years from today, inferred from yields on Treasurys and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS).

Five-year inflation compensation rose to 2.66 percent as of February 20, up about 0.25 percentage points over the past six months and returning to levels last observed in the fourth quarter of 2022, when PCE inflation was close to 6 percent year over year. This increase seems to reflect increases in near-term inflation expectations, which could reflect the temporary effect of tariffs on inflation in the first couple of years of the five-year period.

Unlike the Surveys of Consumers — which showed increases in both near-term and longer-term inflation expectations — market-based measures of inflation expectations do not show an increase in market participants' expectations of the long run. Five-year-forward inflation expectations were 2.24 percent as of Feb. 20, similar to their average level over the preceding six months (2.27 percent) and within the range of prepandemic observations.

What do these data suggest for inflation risks in 2025? Evidence from financial markets and surveys of households and businesses suggest that the risk of a pickup in near-term inflation has increased. On the other hand, responses to the Richmond Fed services survey are a reminder that not all input cost increases will fully pass through to consumer prices. Finally, there is limited evidence that the rise in the near-term inflation outlook has led to a broad reassessment of longer-run inflation expectations: The University of Michigan survey measure of longer-run expectations rose, but market-based five-year-forward inflation compensation did not.

Nevertheless, with the economy still in recovery from a prolonged period of elevated inflation, policymakers will continue to closely monitor these and other data as they consider any additional adjustments to the stance of policy.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.