Auto Industry Has Little Wiggle Room to Navigate Tariff Hikes

On March 26, new tariffs were announced on automobiles and motor vehicle parts. Although the new tariffs are effective April 3 for imported automobiles and by at least May 3 for vehicle parts, it could take time for any effects on consumer and producer prices to become apparent. These policies could have a large impact on the industry: According to data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, no vehicles among 2025 model year U.S.-assembled vehicles consist purely of U.S.-produced content. This week's post looks at some factors that could determine the speed and degree to which tariffs on the automotive industry pass through to consumer prices.

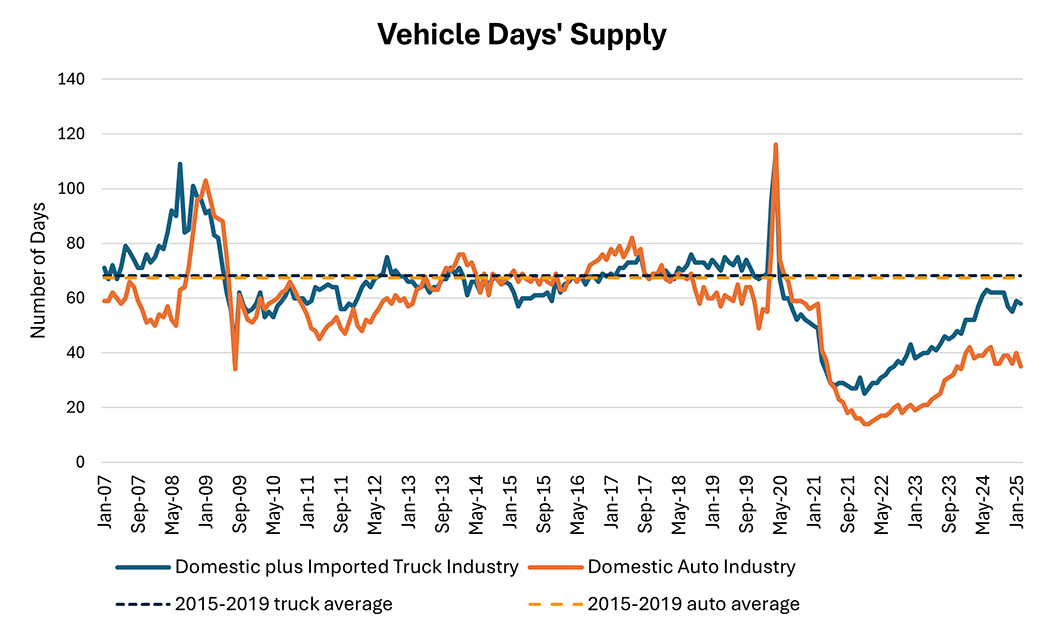

One such factor is inventory conditions. Auto dealers with excess inventories could benefit from the implementation of tariffs by delaying imports of more expensive vehicles until inventory levels normalize. Also, dealers and manufacturers seeking to cushion themselves from the impact of tariffs could pull forward their imports, building up inventories before tariffs are implemented.

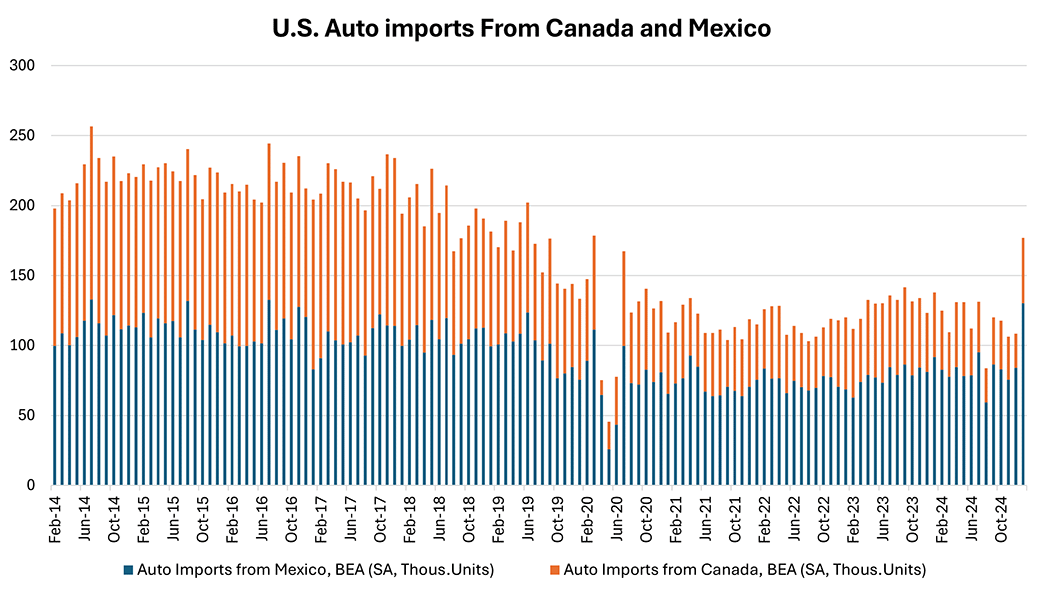

There's evidence that the auto industry pulled forward imports of Canadian and Mexican assembled vehicles ahead of tariffs. According to Bureau of Economic Analysis data, a seasonally adjusted 176,900 autos were imported from Canada and Mexico in January, the highest mark since March 2020. Canadian auto imports rose to 46,700 (compared to 24,400 in December), and Mexican auto imports rose to 130,200 (compared to 84,100 in December).

However, from an overall industry perspective, inventories remain low. Figure 2 shows one measure of automotive inventories: vehicle days' supply, which refers to the average number of days it would take to sell through the current inventory if no other vehicles were added. The figure shows both light trucks (which includes pickup trucks and SUVs, in blue) and autos (which includes passenger cars and station wagons, in orange). Days' supply for both trucks and autos are below their respective 2015-19 averages — indicating vehicle inventories are in short supply relative to prepandemic benchmarks — despite the monthly annualized pace of light vehicle sales remaining slower than 2015-19 average from May 2021 through February 2025. This could indicate dealers are less able to postpone purchases of imported vehicles and delay incurring tariff costs from purchasing new inventory.

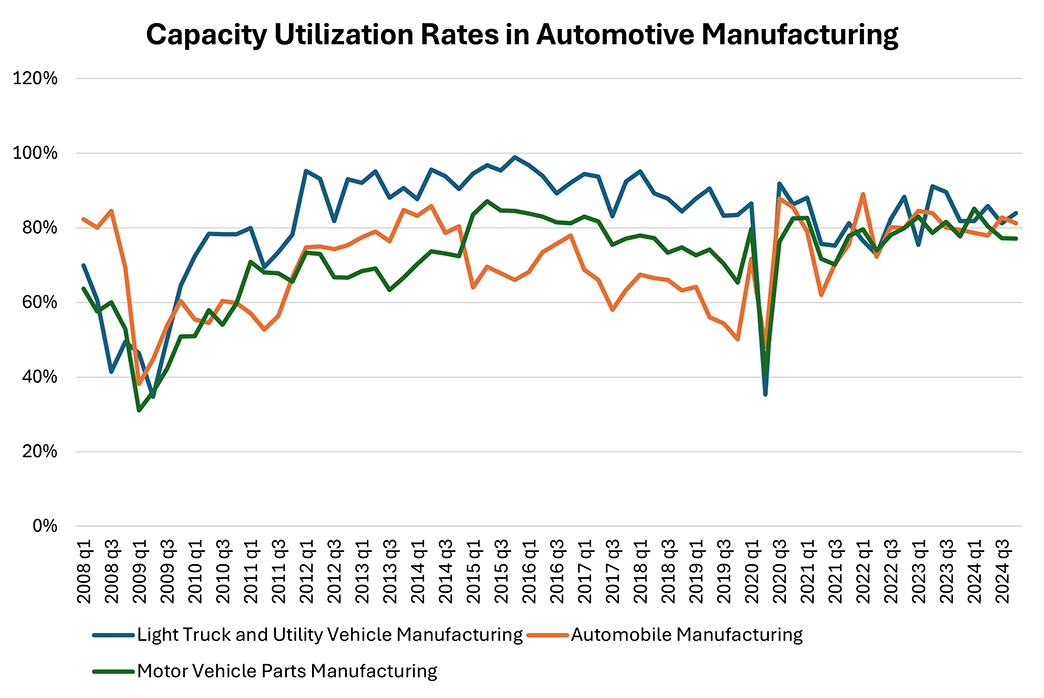

Another factor which could buffer the auto industry from immediate tariff effects is excess production capacity. In theory, an automaker with underutilized factories in the U.S. could ramp up domestic production of vehicles and avoid tariffs. In practice, however, underutilized factory capacity may not be easily substituted across production activities. For example, it may be challenging to convert an engine plant into a final assembly plant.

Figure 3 plots capacity utilization rates for light truck, auto and motor vehicle parts manufacturing. Data are from the Census Bureau's Quarterly Survey of Plant Capacity Utilization. As of the fourth quarter of 2024, capacity utilization for light truck factories was 84.0 percent, compared to 81.3 percent for auto plants and 77.1 percent for motor vehicle parts factories.

While these utilization rates are below 100 percent, from a manufacturing perspective, running at 100 percent utilization is not optimal because it implies that workers and machinery are operating at their limits, leaving no room to maneuver inevitable production challenges that arise. Typically, manufacturers aim for capacity utilization rates between 80-85 percent. By that standard, the auto industry is largely running at an efficient level of utilization, with little room to increase production to sustainably higher levels.

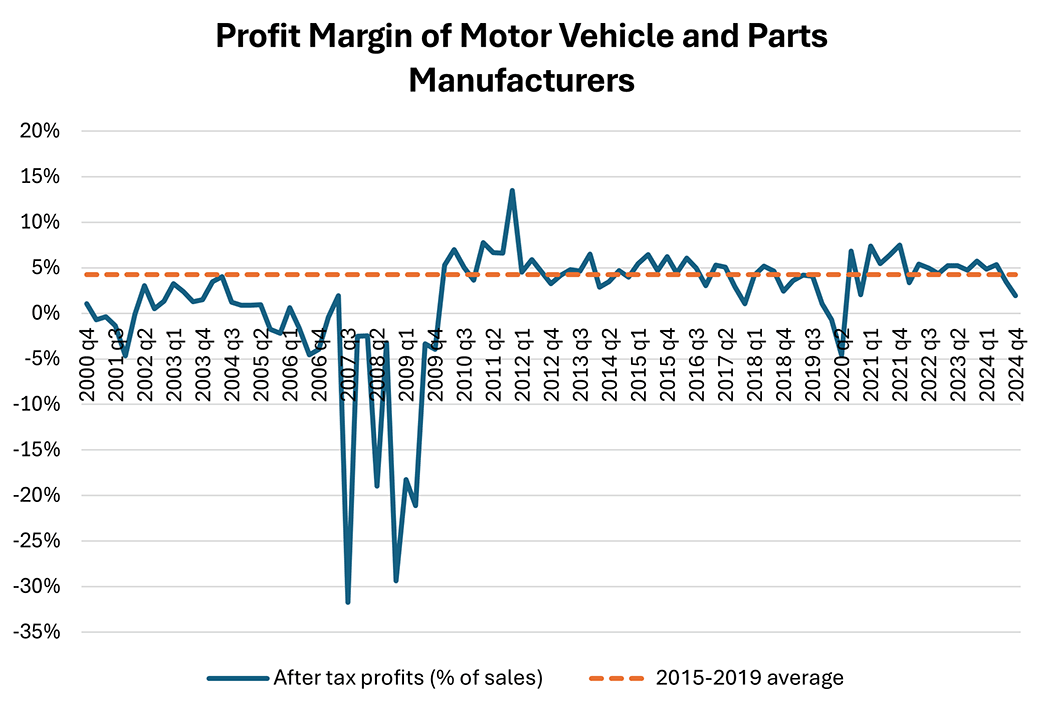

Finally, profit margins could also adjust to blunt the price impact of tariffs for customers, with manufacturers choosing to absorb the higher price of importing vehicles and parts rather than passing it on to buyers. Figure 4 shows the profits margins of motor vehicle and parts manufacturers, computed by dividing after-tax profits by total sales based on data from the Census Bureau's Quarterly Financial Report. As of the fourth quarter of 2024, manufacturers of motor vehicles and parts saw a profit margin of 1.9 percent, compared to a 3.5 percent margin in the previous quarter and a 2015-19 average profit margin of 4.2 percent. With current profit margins below recent benchmarks, manufacturers may be less well-positioned to absorb higher input prices via lower margins.

With vehicle days' supply low versus prepandemic levels, factories running at generally efficient levels and recent automaker profit margins low, the auto industry appears to have little wiggle room to cushion consumers from tariff impacts. These findings suggest that car buyers might feel the effects of tariffs sooner rather than later.

Please note: Macro Minute will be taking a break next week.

Views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond or the Federal Reserve System.